When I was hyping myself up to write the second article on my website after almost 3 years I naturally had a look how I can busy myself with everything else but writing the actual article (while still fooling myself into believing this is a necessary preparation for … just writing the blimmin’ article. But I think the work in my website generation laboratory was worth the fuzz this time, as I quite enjoy the new workflow. I now can write code sprinkled articles in a Jupyter notebook and have them rendered automatically into my lektor generated website using a bit of Python code hooked into lektors plugin system.

It is a never ending story: every time I want to write an article to publish on my website, I change my blog engine instead. At some point I even created my own static website generator. All this fuzz just to avoid actually writing things to … you know … put on a website :). This might be excused by the fact that I really enjoy spending my leisure time tinkering with things aimlessly rather then actually producing something that might be useful, but I finally started seeing through my evil self-sabotage mechanisms and was determined to put a stop to it! So I did the natural thing: I went to my lab [1] and tinkered with the engine.

Prologue 🔗

I played with a lot of blog engines over the years - while never really blogging anything. I mostly work in backend development, but there is something that fascinates me about web design and web development. It’s one of these things I guess :).

I am particularly fond of static website generators that provide a workflow that is similar to developing software. I played with pelican, jekyll, hugo, nikola, flask + frozen-flask and the lot. As already mentioned: I even wrote my own sphinx based generator … while still never really blogging anything.

At the beginning of 2017 I made a deal with a colleague that I would finally write a blog article about the pytest development sprint and a bit about my involvement. It would have been boring though if I would have used the site I had already online (last incarnation was a simple mkdocs driven thing). It would also have been boring to use one of the engines I already knew. Using something utterly profane like medium or wordpress was obviously completely out of the question! I mean, I could have just written the article then and be done with it. Who wants that? Right. Not me. So I started looking around for the next thing that could keep me from writing that article and I stumbled over lektor. Now this was something that could keep me busy for a while as it is not simply a static website generator, but rather something that you can use to build a static website generator with - a website generator generator! Long story short: I set that up from scratch with a simple sass style, wrote a little plugin to integrate that into lektors development server, and finally actually wrote and published that article. Nobody ever made a deal with me again that forced me to write another article, so that was it. I had unlocked the “i-have-a-blog-but-i-never-blog”-achievement once again - only on a higher level. Until very recently.

Because very recently I realized that I had produced a lot of material while trying to teach Python and test automation to all kinds of folks over the last years. I finally wanted to start sharing some of these materials on my website. As making strange deals seems to work with my contorted psyche, I made a deal with myself to publish at least one article a month for at least a year.

This time I was determined to resist the temptation to start from scratch and resolved to adjust the existing setup to fit my new needs. The new needs arose from the fact that I work mostly in Jupyter Notebooks nowadays, when creating learning materials and I like it, so I want to write articles like that and have them integrate into my website.

Jupyterizing Lektor 🔗

If you don’t know Lektor at all yet, here is the minimum amount of knowledge necessary to follow this article:

To build a page, Lektor takes a folder, a data model defined in an .ini and a Jinja2 template. The folder for the page needs at least a contents.lr file - a simple lektor specific text file format. This file contains data that fits the user defined data model. Usually this is some meta data about the content and the main content of the page formatted in markdown.

Lektor is extensible via a plugin system that involves creating an installable package and implementing some methods in a class inheriting from lektor.pluginsystem.Plugin. Methods in that plugin class will be called, when Lektor emits events in different phases of the build process.

Did someone else solve my problem already? 🔗

To integrate Jupyter notebooks, there is already a plugin that hasn’t been worked on for a while and is more of a prof of concept. It was a good starting point though to see what it does and to decide what I want:

- It is not cooperating with Lektor in the way that changes in the notebook file are not detected by the build system, making it necessary for the

contents.lrfile to be changed to trigger a new page build. I want this to work correctly. - It renders

.ipynbfiles directly to HTML usingnbconvertwith thebasictemplate. [2] I don’t want to struggle with HTML and CSS to make the rendered notebook fit the style of whatever theme the web page has. I also want all the markdown features available that Lektor and a whole range of plugins offer. I also want the style of the rendered notebook to automatically fit the rest of the web page. - The notebook is not executed before rendering it. I want to be able to do that. I also want to have the possibility to prevent specific cells from being executed.

- Which notebook should be used, can be chosen from the attachments in the CMS UI. This sounds nice at first, but makes it more complicated (and I don’t use the UI at all). I want this instead: if a page is “notebook driven” should be detected automatically via a file name convention (

notebook-file name without extension == page name). - The code uses the Python descriptor protocol and some involved caching logic, which both looks like advanced black magic to me and still does not play nicely with Lektor, so there might be potential for simplification. I think the main problem is, that the plugin is a slightly adjusted copy of the original

Markdownclass which is used to render markdown content incontents.lr, so I suspect that this is actually defeating the purpose instead of helping it. I want code that works and is easier to understand.

Not really, so I created my own 🔗

lektor-jupyter-preprocess is a Lektor plugin that does the following:

- Automatically detect when a page is “notebook driven” via a fixed file name convention: if the page is called

my-pageand the page folder contains amy-page.ipynb, thecontents.lris generated from that notebook (e.g. see the page folder for this article). - Automatically trigger a rebuild when any file in the page folder changes.

- Execute the notebook before rendering it (individual cells can be excluded via cell metadata).

- Apply the

%loadcell magic before executing to update dependent code from other files. - Render the notebook into

contents.lr. The rendered notebook is markdown. Lektor can then treat this as if it was a hand writtencontents.lr.

How does it work? 🔗

99.9%: existing ecosystem, 0.1% wrapping it to integrate it into Lektor.

Generating well formed markdown 🔗

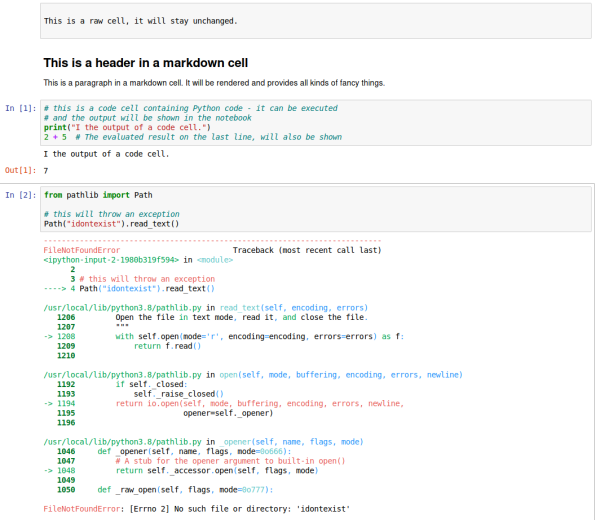

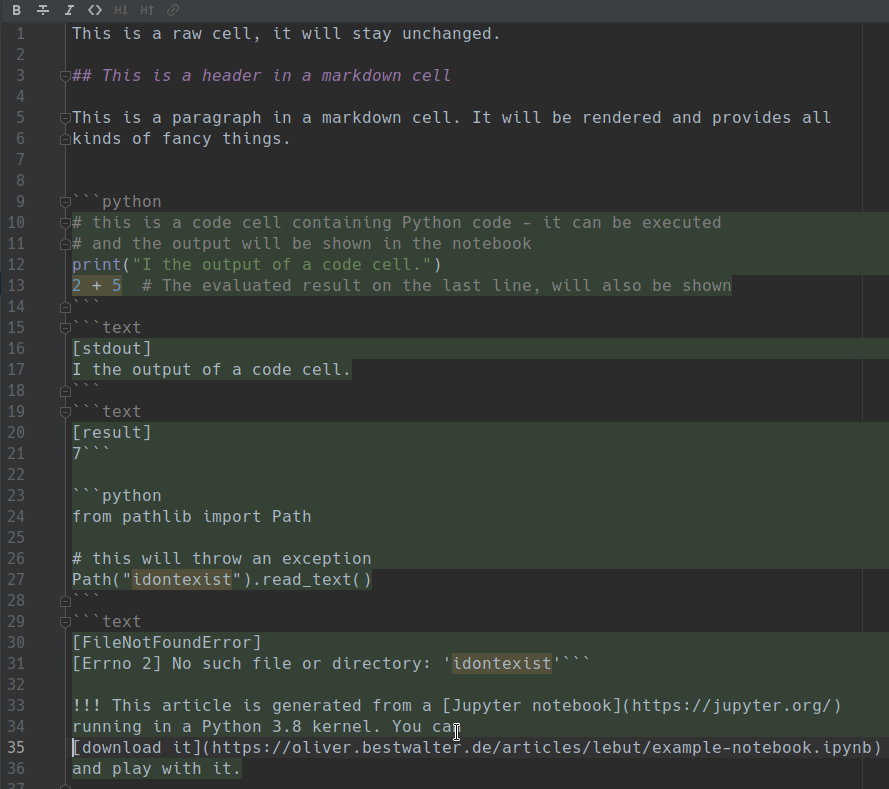

Generating markdown from a notebook comes out of the box via nbconvert - so if you take a notebook that looks like this in the browser:

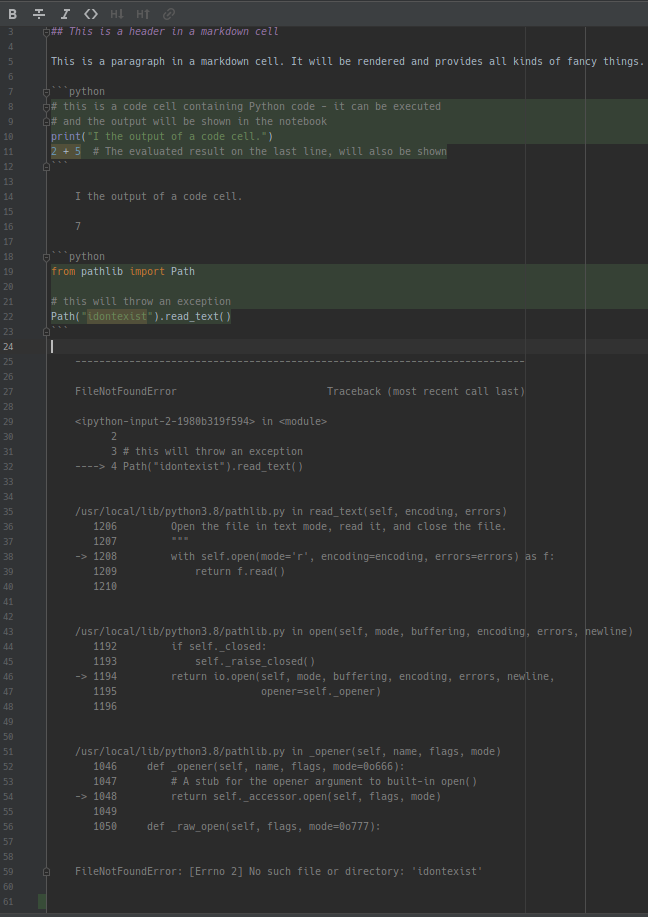

… and convert it with jupyter-nbconvert --to markdown example-notebook.ipynb, out drops an example-notebook-markdown.md that contains this:

This is somehow already what I want, but I want the output to be marked properly and I don’t want the whole traceback - just the name and message of the error is enough. So there is a little bit of massaging to be done. The question is: when should that happen? I could try to massage the generated output to my liking, but I’d rather poke a finger into my eye, so this has to happen when I can still work with the data.

Thanks to the friendly Jupyter Development Team, nbconvert is written in a way that it is not too hard to make this possible by inheriting from ExecutePreprocessor. This lets you hook into the execution of individual code cells and massage the contents there. So this is what I came up with:

# %load -s ArticleExecutePreprocessor ../../../packages/lektor-jupyter-preprocess/lektor_jupyter_preprocess.py

class ArticleExecutePreprocessor(ExecutePreprocessor):

"""Apply load magic and massage the markdown output."""

def preprocess_cell(self, cell, resources, *args, **kwargs):

if cell.cell_type != "code" or not cell.source.strip():

return cell, resources

cell = pre_process(cell)

cell_config = {

**config,

**self.nb.metadata.get(PLUGIN_KEY, {}),

**cell.metadata.get(PLUGIN_KEY, {}),

}

log.debug("final config for cell is:\n%s", config)

language = self.nb.metadata.kernelspec.language

if config["metadata.blackify"] and language == "python":

cell.source = blackify(cell.source)

if cell_config["metadata.execute"]:

nodes = self.run_cell(cell, *args, **kwargs)[1]

else:

nodes = cell.outputs

cell = post_process(language, cell, nodes, cell_config)

return cell, resources

# %load -s pre_process ../../../packages/lektor-jupyter-preprocess/lektor_jupyter_preprocess.py

def pre_process(cell):

"""Apply magics and update cell level config overrides."""

cell.source = cell.source.strip()

if not cell.source:

return cell

assert isinstance(

cell.source, str

), f"bad source type: {type(cell.source)}"

lines = cell.source.strip().splitlines()

load_candidate = lines[0].replace("# ", "")

# TODO apply other magics (e.g. %%capture)?

# also: is there a more "official" way?

if load_candidate.startswith("%load"):

try:

metadata_override = lines[1]

except IndexError:

metadata_override = None

if metadata_override:

try:

metadata_override = eval(metadata_override)

except Exception:

log.exception(f"[IGNORE] eval of '{metadata_override}' failed")

if isinstance(metadata_override, dict):

cell.metadata[PLUGIN_KEY] = {

**cell.metadata.get(PLUGIN_KEY, {}),

**metadata_override,

}

cell.source = apply_load_magic(load_candidate)

return cell

# %load -s post_process ../../../packages/lektor-jupyter-preprocess/lektor_jupyter_preprocess.py

def post_process(language, cell, nodes, cell_config) -> nbformat.NotebookNode:

"""Construct what should be written to the contents for this cell.

This simply creates a new raw cell containing everything - not because it's the

best solution but the easiest for my use case.

TODO figure out a better way that also accommodates potential HTML/interactive

output better Modifies cell in-place (#4).

"""

out = [config["cell.source"].format(language=language, cell=cell)]

for node in nodes:

assert isinstance(node, nbformat.NotebookNode)

# https://nbformat.readthedocs.io/en/latest/format_description.html

if node.output_type == "execute_result":

out.append(config["node.execute_result"].format(node=node))

elif node.output_type == "stream":

# TODO use tags/raises-exception like in pytest (not raising raises error)

# if <wherever that tags thing is> is set:

# raise DidNotRaise(f"should have raised but didn't:\n{node}")

out.append(config["node.stream"].format(node=node))

elif node.output_type == "error":

if not cell_config["metadata.allow_errors"]:

raise ErrorsNotAllowed(

f"raised but errors not allowed:\n{node}"

)

if cell_config["metadata.full_traceback"]:

# TODO handle ANSI terminal colors stuff

# see if how jupyter does it is reusable

# to keep colours this would need to be HTML though

out.append("".join(node.traceback))

else:

out.append(config["node.exception"].format(node=node))

else:

raise UnhandledOutputType(

f"{node.output_type=} unknown - {cell.source=}"

)

return nbformat.NotebookNode(

{"cell_type": "raw", "metadata": {}, "source": "\n".join(out)}

)

This is how it is configurable at the moment:

# %load -r 23-50 ../../../packages/lektor-jupyter-preprocess/lektor_jupyter_preprocess.py

PLUGIN_KEY = "JUPYTER_PREPROCESS"

config = {

"url.source": None,

"metadata.blackify": True,

"metadata.execute": True,

# todo figure out how jupyter does these things and play together with it

"metadata.allow_errors": False,

"metadata.full_traceback": True,

"cell.source": "\n\n```{language}\n{cell.source}\n```",

# TODO figure out, why node.data[text/plain] is correct (no quotes around key!1?!?)

"node.execute_result": "```text\n[result]\n{node.data[text/plain]}\n```",

"node.stream": "```text\n[{node.name}]\n{node.text}\n```",

"node.exception": "```text\n[{node.ename}]\n{node.evalue}\n```",

}

f"""configuration of the plugin.

This dict should define all existing keys and provide sane defaults (sane for me).

It can be overridden in these ways (sorted by order of precedence - last one wins):

* config values from configs/jupyter-preprocess.ini

* dict at {PLUGIN_KEY} in notebook metadata

* dict at {PLUGIN_KEY} in cell metadata

* dict literal on second line in a cell using the %load magic

See example-project/jupyter-preprocess.ini and tests/code.ipynb for examples

"""

The idea is to hook into the part of the conversion process where the notebook is preprocessed before the actual conversion to markdown.

In my case the necessary preprocessing means:

- For each individual code cell:

- (optional - on by default) format the source code with black

- if it contains a

%loadmagic: execute it to load the code from the file into the cell (always - commented out or not) - (optional - on by default) execute the code

- (configurable) format the outputs

The complete plugin code is in lektor_jupyter_preprocess.py

If I run this through nbconvert now, the generated markdown looks like this:

That’s more like it and I can tweak and extend the conversion process, whenever I need to.

Lektor plugin 🔗

The first incarnation of this used the before-build event that is called indiscriminately before a source is built. This caused an eternal build loop when generating the contents.lr from a notebook. I prevented this by adding caching to detect if the notebook had changed since the last build. This worked but was ugly. I had set out to only make this work, so I decided I was finished. The next weekend though I couldn’t help but having another look.

The current incarnation adds a new build program that slightly modifies the attachment build behaviour for “notebook powered” pages to preprocess the notebook as part of the normal build process. Still not knowing much about Lektor this might be less wrong, but more importantly: it works reliably without needing extra caching, and is easier to understand in the context of a build. I also like it more, because this motivated me to look a bit into how Lektor works. Which was very interesting.

These events are used in the plugin:

setup-envis used to prepare the system on startup. This is when config values of the plugin can be populated for later use by the templates and when specialized build programs can be added.before-buildis called for all sources before it is decided if a build of that source actually needs to happen, this is why it is not very useful to do any actual preprocessing there (that then might not be necessary and create a build loop as mentioned), but it can be used to provide more context for the build templates - in the case ofjupyter-preprocess, whether the page that is about to be built is generated from a notebook or not.before-build-allinitializes an in-process cache to prevent duplicate builds if several artifact are updated at once (e.g. after alektor clean) - there might be a better way to do all this via Lektors dependency tracking on the context but I didn’t have the chance yet to look into this closer - I also have a hunch that turningcontents.lrinto a build artifact itself like the plugin is doing it, breaks a lot of assumptions and needs some special handling anyway.

This is what the plugin class looks like:

# %load -s JupyterPreprocessPlugin ../../../packages/lektor-jupyter-preprocess/lektor_jupyter_preprocess.py

class JupyterPreprocessPlugin(Plugin):

name = "Jupyter Notebook preprocessor"

description = "Execute and render a Jupyter notebook. Provide the result in contents.lr."

def on_setup_env(self, **_):

"""'Replace' attachment build program with an enhanced version.

`get_build_program` finds this before the inbuilt, effectively shadowing it.

This makes the preprocessing a part of the build of the page, overwriting

contents.lr before it is processed, therefore preventing build loops.

"""

update_global_config(self.get_config().to_dict())

self.env.jinja_env.globals[PLUGIN_KEY] = {

"url_source": config["url.source"],

"paths": set(),

}

self.env.add_build_program(

Attachment, NotebookAwareAttachmentBuildProgram

)

def on_before_build_all(self, **_): # noqa

_already_built.clear()

def on_before_build(self, source, **_):

attachments = getattr(source, "attachments", None)

if not attachments:

return

attachment = attachments.get(f"{Path(source.path).name}.ipynb")

if attachment:

self.env.jinja_env.globals[PLUGIN_KEY]["paths"].add(source.path)

If you want to try it in your Lektor project 🔗

In the simplest case:

- install it into your Lektor project, create a new folder and in it a Jupyter notebook with the same stem - e.g.

<your project>/content/my-notebook-test-page/my-notebook-test-page.ipynb - edit your notebook wherever you like while having

lektor serverunning - see how the page gets generated from the notebook

Keep in mind that the complete contents.lr gets rendered from the notebook, so you need to create the same structure like a normal contents.lr would look like (for my use case this is just right atm, but it would be not too hard to extend that in a way that the generated markdown does not clobber the file if it finds a special marker where to put the generated markdown inside the contents.lr). [3]

Additionally to generating the notebook the plugin injects the global variable JUPYTER_PREPROCESS into the jinja template which at the moment contains:

- the source link (if set in

configs/jupyter-preprocess.ini) or a direct link to the jupyter notebook attachment - info about whether the page that is about to be rendered originated from a notebook (to link to the original for example (like you can see at the bottom of this page))

Here is how a footer with a link could look like using that data:

<footer>

<div class="origin-hint">

{% if this.path in JUPYTER_PREPROCESS.paths %}

{% if JUPYTER_PREPROCESS.url_source is defined %}

<a href="{{ JUPYTER_PREPROCESS.url_source }}{{ this.path }}">

generated from a Jupyter notebook — view sources

</a>

{% endif %}

{% endif %}

</div>

</footer>

See this small example project to see how it works in the simplest case

tox based development and publishing workflow 🔗

To cap it all off: if a project hasn’t got a tox.ini that wraps all important activities of the project into a neat package it doesn’t feel like a real project. So this is what tox -av tells me about the workflow of my Lektor project (in case I don’t write another article for the next three years and I come back to it and have no idea how stuff works 😉):

$ tox -av

default environments:

serve -> run custom wrapper around the lektor server

additional environments:

clean -> tidy up to start from a clean slate

build -> build the website at ../build

serve-build -> serve ../build at http://localhost:7777

serve-notebooks -> serve jupyter notebooks

deploy -> build and push master (website build) to github

test -> run tests for lebut

Epilogue 🔗

Now I have a reasonably pleasant workflow to turn my notebooks into website articles. I am pretty confident that I will be able to keep that deal with myself :).

Can anyone tell me from which film this gif is? I found it on tenor and would like to give proper credit [⤴]

This seems to be the the usual approach though, when looking at other blog engines. For Nikola there is a theme with inbuilt Jupyter support. Same for pelican. [⤴]

there is already an issue for that - I might actually do that soonish, because having raw cells in the notebook that contain Lektor data is kinda ugly. [⤴]